Or How I Did Not Kill Kevin Bakin

I don’t remember exactly how old I was the first time that I tried real San Francisco sourdough bread, but I was pretty young – maybe six or seven. It’s one of those memories that, despite its clarity, has those fuzzy edges that go along with early childhood memories. I remember I was with my parents, and we had come to California to see my dad’s BFF and his family. We were staying at their house, and Bill and Aileen had just been to San Francisco for the weekend so they brought back fresh sourdough; the kind that you finish baking in your own oven so that it’s good and hot. Now that I think about it, that may have been the first time that I had freshly baked bread. It’s the first that I remember, anyway. I can’t say for certain that I had never had sourdough prior to this experience, but this was the first time that it was “real San Francisco sourdough,” and everyone was making such a fuss that I knew it must be something special. Needless to say, I understood what all the fuss was about.

At the time I was not aware of the process behind making sourdough, and was more than a little shocked when I first heard it. Two days to make a loaf of bread? That seemed a little excessive. Granted, I was never much of a baker, so to me two days just seemed like a lot of time to screw something up and have to start all over. I also was not aware that sourdough was not a “San Francisco thing” (so ‘Murican of me).

Leavening with a fermented starter is actually just how bread was made for millennia. Archaeologists in Egypt have uncovered evidence of wheat processing as far back as 8000 BCE, and evidence of leavened bread at about 3600 BCE. That’s the way it was done until some industrious lush discovered that barm – the foamy stuff that forms on top of fermenting liquid – could also be used as a levain, with much quicker results. As often happens with new technological knowledge, traditional methods fell out of favor, and for a time true sourdough could only be found in a handful of monasteries. Luckily, sourdough starters became popular again during the 19th century as folks came west in search of their golden fortunes, and then again in recent years as peeps have begun seeking out more naturally nutritious and tasty alternatives to what passes for bread on a grocery store shelf. And it was the combination of these events that led to my first starter, Kevin Bakin, who came from a 100+ year old starter from Eastern Montana.

I was so curious to learn how the bread was made, not thinking initially that it was something I was ever going to attempt on my own. But then, it was so easy! And while it does take about two days, the bulk of those two days is simply waiting for stuff to rise. And what beautiful rising it was. The only problem? It wasn’t sour. There was the tiniest hint of lingering sourness at the very end, but it didn’t have that sharpness so characteristic of the sourdough I had fallen in love with as a child. But it was really, really, good bread. It smelled like heaven, and it had that perfect, magical crust which made that perfect, magical sound that is the hallmark of any Parisian baker worth their salt. So I brought it back to the Bay and began researching ways to make sourdough more sour. I figured if there was any place in the world to figure it out, this would be it. My sister and I had already tried a few tricks to get it more sour, and nothing worked, so we wondered if maybe it wasn’t a question of terroir. It wasn’t San Francisco sour because it wasn’t in San Francisco.

So I brought Kevin home and dove into the list of about twelve different “tips” for making sourdough more sour. Nothing worked. I tried all different kinds of flours, I tried changes in the environment during the feeding and the rising stages, I tried letting it sit, unfed, for longer periods of time so that there was more hooch to mix in (the “hooch” is the alcohol that forms on top of the starter when it begins to separate), I tried everything I read. Nada. Always really good bread, just not sour. My sister tried a few different methods as well, but always with the same result: really tasty, not-sour, sourdough.

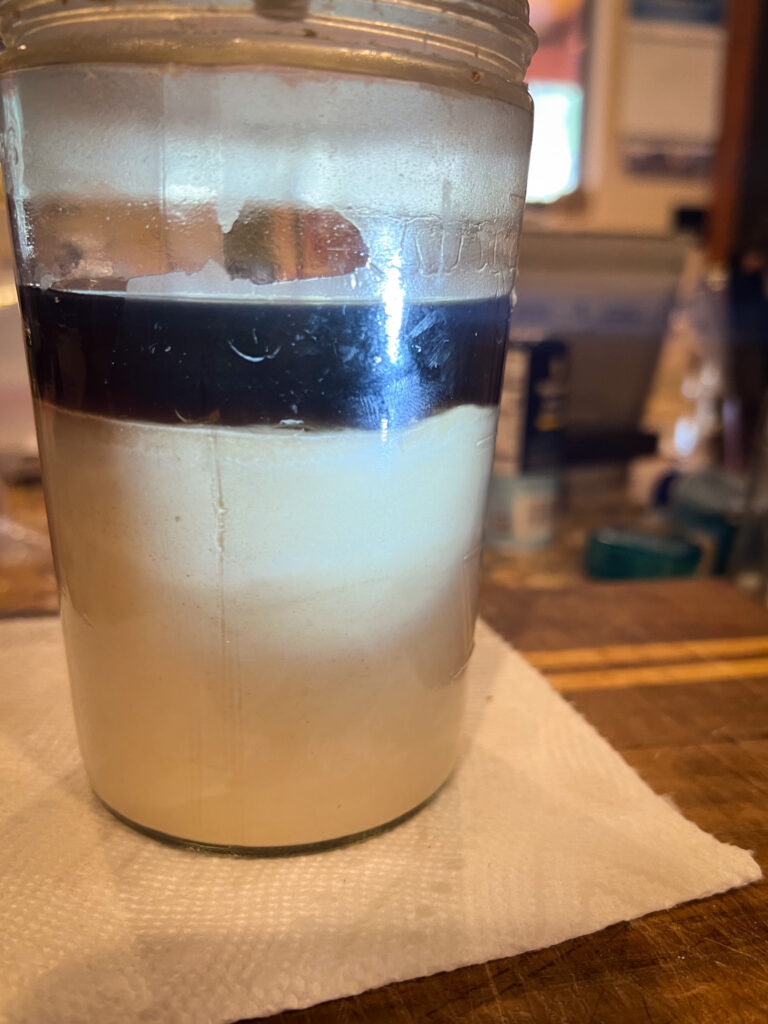

For a time we just rolled with it. The bread was good; perhaps we would find another starter someday that produced a more sour bread. Imagine our delight when our father’s neighbor told us about some really old sourdough starter she had in the back of her refrigerator. She thought it was most likely dead with no hope of resuscitation, but my sister and I told her to bring it to us and we would bring that sucker back. She brought us the jar and it did have some of the blackest hooch I had ever seen. But it turned out that it was only mostly dead, and we were able to fully rejuvenate it.

This is where I should mention that if you have heard keeping a sourdough starter is difficult and time consuming, it’s not. Perhaps there are certain atmospheric conditions which require consistent feeding, but my sister and I have both left our starters unattended for weeks – sometimes months – and it comes back after a feeding or two. Do NOT think that you can’t have sourdough starter because you don’t have time to care for it daily. The one from our dad’s neighbor hadn’t been fed in over a decade, and we had it frothing in about three days.

Thus was born Kyra Breadwyck, who also made tasty and delightful bread, with all of those magical properties that we love so much.

But still not sour.

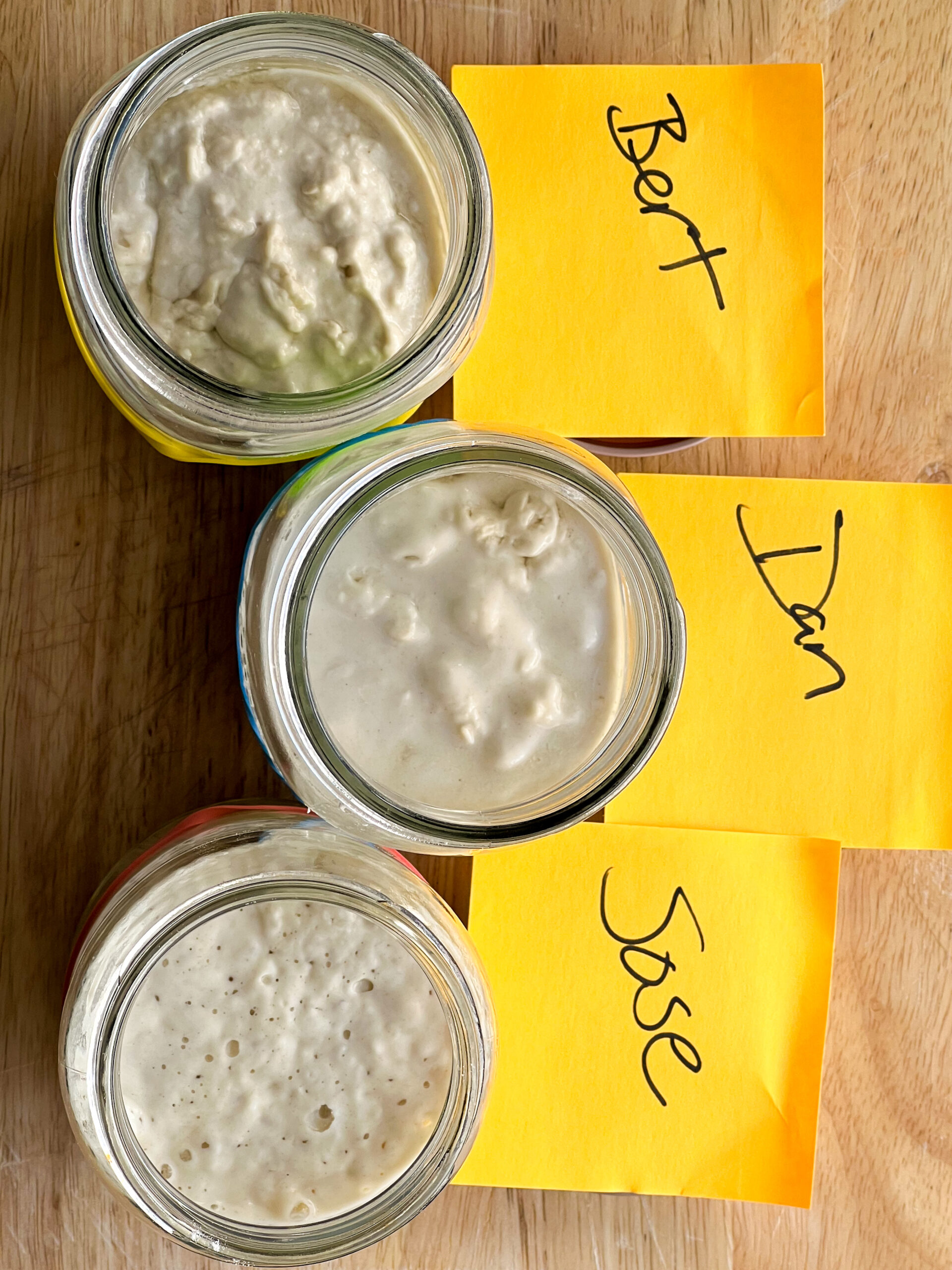

Finally, after months (years) of monkeying around with suggestions from the inter- webs, it dawned on me that perhaps the relative sourness is deeper into the terroir than I had imagined. Perhaps whatever is in the San Francisco air that makes the San Francisco sourdough has to be there from inception (sometimes I’m a little slow on the uptake; turns out there is a sourdough bacterium specifically named for San Francisco. I always sucked at chemistry). So when I found myself with some extra time, I looked into how difficult it would be to make my own starter from scratch. It’s not difficult at all. It takes some patience and it can be messy, but one could almost do it by accident. Nevertheless I followed all of the steps – to the letter – and after about two weeks I was ready to bake with my very own starter, Sosie. And Sosie is pure San Francisco. I suppose technically “Bay Area,” but whatever, she is sour AF. All of the same great attributes of the other starters – the heavenly smell, the chewy goodness inside, the crust… but with that very recognizable San Francisco tang. So happy.

Cheers to Sosie; long may she ferment.