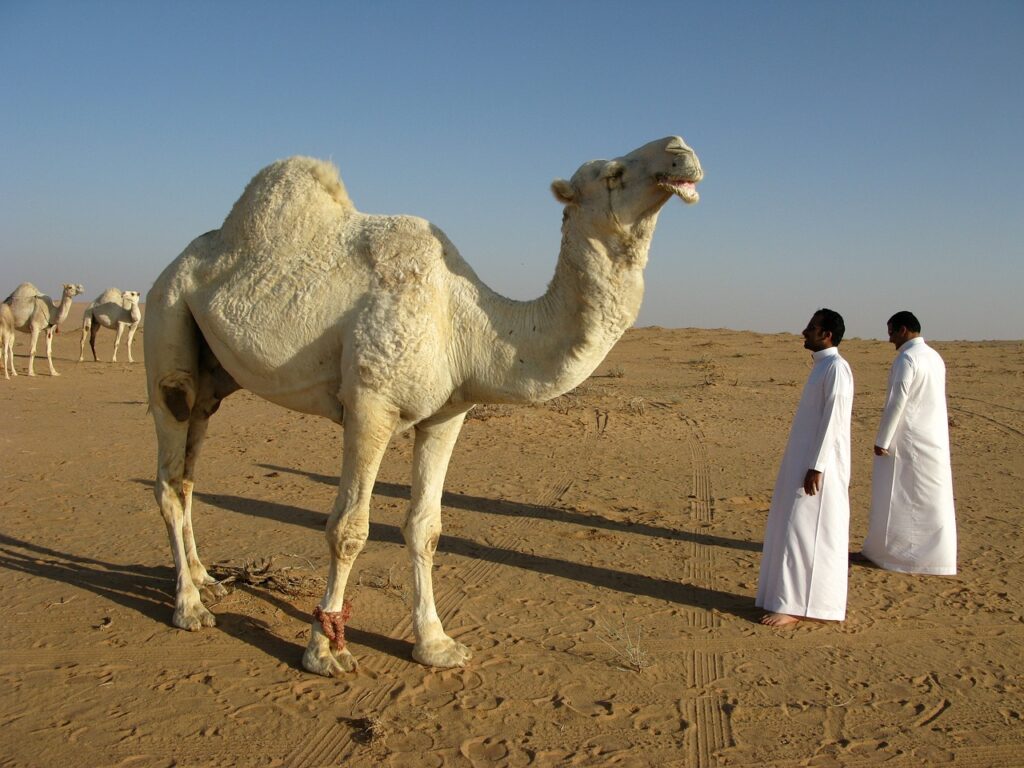

I often find myself wondering about random things: animals, plants, how many bodies are encased within the Great Wall of China (depends on who you ask). Not long ago, it was camels. I’m not sure what triggered my sudden interest in these silly looking creatures, with their permanent smirks and their gangly legs and their big, crazy feet (wait… is the camel my spirit animal?). But I found myself going beyond my usual wikipedia skim and getting curious about their quirkiness. It turns out that camels are wildly fascinating. I had never stopped to ponder the adaptations that made them so well suited for the climates in which they are found. Camels can literally (and I mean that in the literal sense, not the millennial sense) go months without water and then lap up 30 gallons in about 13 minutes. Contrary to popular belief, however, the hump does not store water; It stores fat – up to 80 pounds of fat – that they can use during long trips with limited water and food supplies. The secret to their ability to function with limited hydration isn’t about storing water, it’s because they are highly specialized in conserving it. Their systems are so highly specialized that their kidneys essentially shut down when the animal is without water for an extended period, and are then able to return to normal function within 30 minutes of rehydrating. I won’t share what happens to their urine during these long spells, because it’s really gross, but it is an amazing feat of evolutionary engineering.

Why the junior high lesson about camels, you ask? Well, why not? I don’t know about you, but I’ve come to the point where just skimming the headlines brings on a minor panic episode – forget actually reading the articles. Just when it’s gone from bad to worse, something else blew up, someone else got robbed, yet another candidate joined and/or dropped out of the election circus. I find it amusing that mental health professionals are advising their patients to “turn off the news.” I mean, I get it and it’s good advice, most days, but if we all follow it then we are exponentially increasing the number of uninformed morons blindly wandering around our streets… perhaps the conspiracy theorists are on to more than the rest of us realize? I digress. I was talking about camels.

I’ll be honest; I now know more about the camel than I ever thought I would care to know. And I likely know a lot more than I will ever need to know. For example, all of the camel’s highly specialized adaptation began right in our own backyard. Evidently, the story of the camel began in North America, too many millions of years ago for me to remember very clearly. One day a few decided to see what lay to the north and so-far-west-that-now-it’s-east, and, voila! Bactrian and Dromedary camels. The divergent group managed to find its way across the Bering Land Bridge, when there was still land there to find a way across, beginning some seven to six million years ago. I suppose that’s part of what made them so adaptable, since the Bactrian camel (that’s the one with two humps, now found in China and Mongolia) can live in extremes as low as negative 20 degrees Fahrenheit and as high as 120 degrees Fahrenheit (all of that sounds miserable – I’d make a terrible camel). There is evidence in the archaeological record that enough of the camel’s ancestors remained on this continent to encounter the first human beings to arrive. The North American camel was, therefore, extinct by about 13,000 years ago.

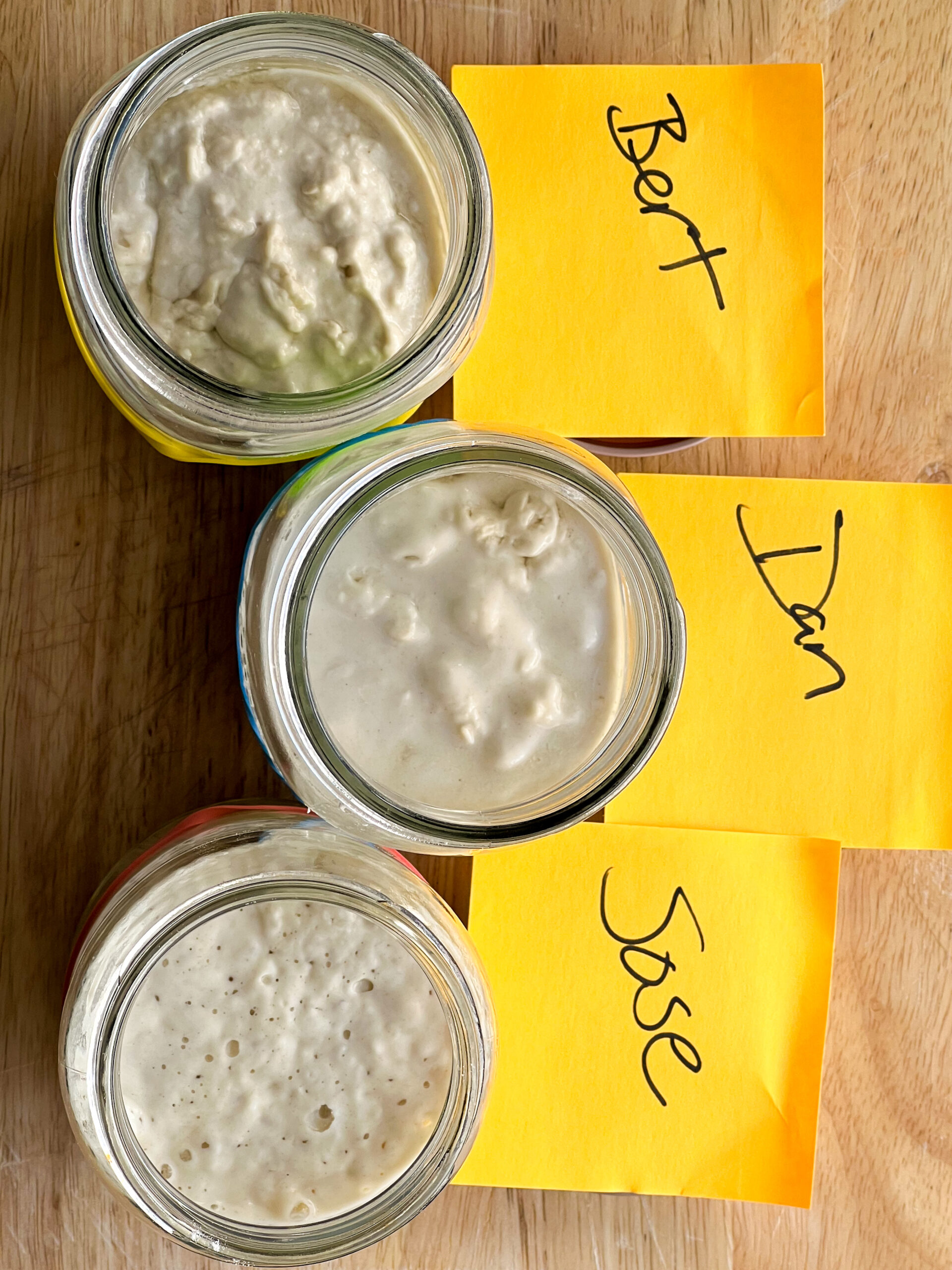

Fortunately, their cousins who made it into Asia and the middle east are still around today, providing nourishment, warmth, and, I have to think, comic relief to those that raise them. Recently, there has been a movement in parts of Africa where extreme drought is a constant threat, to encourage the nomadic and tribal peoples of the area to raise camels in lieu of more water reliant livestock. While this seems like a good idea in theory, there are several surprising obstacles facing its implementation. The first of these is a general stigma that comes with raising camels in certain regions. Camel herders are often looked down upon as “barbaric,” or “backward.” (Unfortunately, it’s not the camels that make some of these people “barbaric”; it’s their propensity for mutilating their baby girls. But that’s a rant for another time). This stigma has eased somewhat since the late 1980s when many of the nomadic, herding peoples of Northern Africa suffered a drought and subsequent famine so intense that millions died of starvation. The vast majority of those that kept camels were spared. This is largely because of the camel’s unique ability to survive not only with minimal water, but by eating plants that no other animal in the region (or, possibly, any region) can touch. The camel can, therefore, continue to produce milk that is highly nutritious and which has a shelf life that is seemingly indefinite.

On the surface, the decision to raise camels seems a no-brainer. But another big obstacle facing their adoption is their environmental impact. While their ability to conserve water and other resources is ideal for desert lands with little to no competing wildlife, the introduction of camels can devastate other ecosystems. In Australia, where the camel was imported from Saudi Arabia in the late 19th century to conquer the Outback, now wild camels have wreaked havoc in the very Outback they were meant to tame. A group of thirsty camels can easily and quickly drain a watering hole that normally supplies many different species over a long period of time. Thus far, Australia’s solution has been to shoot the poor creatures from helicopters. But that, obviously, left the Outback littered with decomposing camel corpses. Fortunately, a group of industrious Australian ranchers came up with a better plan. They use those same helicopters, along with ground crew on ATVs and in pickups, to herd the animals into pens. The camels are subsequently sent back to Saudi Arabia, where they are highly valued as racing camels. Evidently, several generations in the wilds of Australia has made these Dromedary (one hump) camels heartier than their true Arabian counterparts.

But enough about famine and devastation and solving all of our problems with firearms. Let’s check out Turkey (the country). Turkey may be home to my favorite camels, the Tülü, which are a hybrid of the Dromedary and Bactrian, and are bred specifically for wrestling. Yes, camel wrestling. If I ever get to Turkey I am planning my entire trip around witnessing this spectacle. In “Ships of the Desert,” the filmmakers spend a fair amount of time with a camel called Cirkin and his owner, Nurcan Memeci, who lives and breathes for this behemoth of an animal (he is pretty cute). The wrestling, and the festival that goes along with it, occurs in winter, during mating season, when the males need to expend extra libidinous energy but cannot mate (the Tülü are capable of mating, but their offspring are, shall we say, not ideal). While there is obviously some inherent danger in the wrestling arena due to the size of the animals – the hybrids are bigger than either of their parents, some as big as 2200 pounds – there is no award beyond bragging rights, and great care is taken to keep the animals from harm. The camels are themselves the prize possessions of their owners, who spoil them enough to be the envy of Paris Hilton’s chihuahua. Funny, for a breed that was created for their extra heartiness and adeptness traversing the gnarliest parts of the silk road.

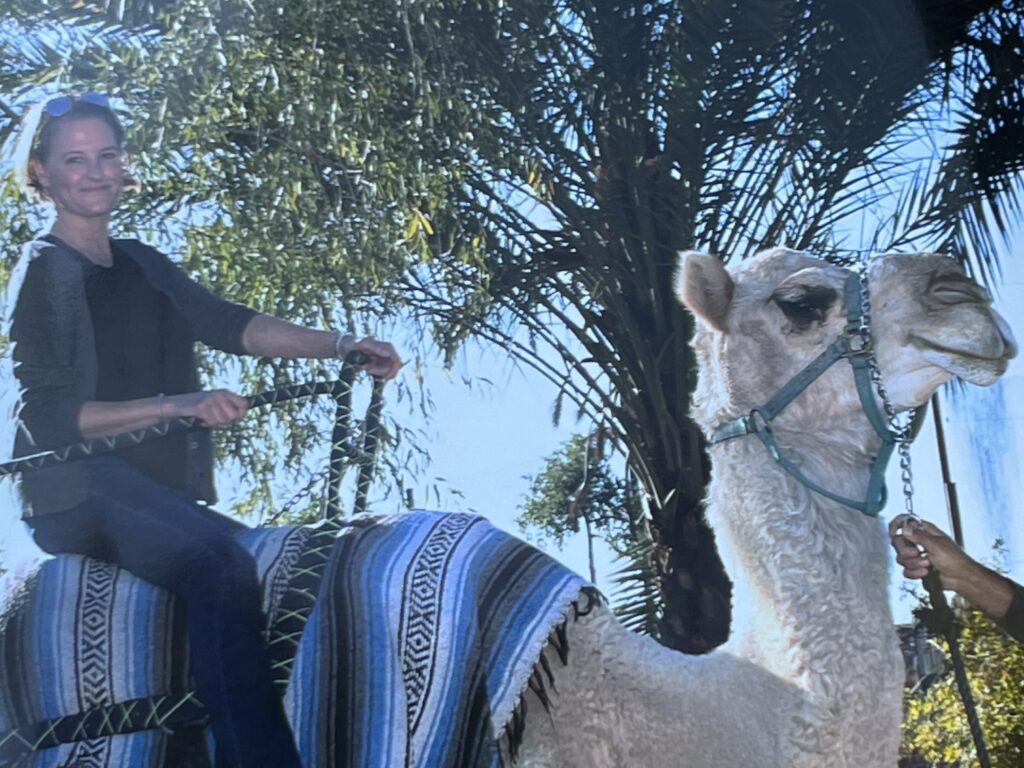

Recently, I had the opportunity to ride a camel. I say “opportunity” as if it were something cool. It wasn’t. I was at the zoo. There were camel rides and no one was around so I thought, why not? My camel’s name was Crockett and he was hysterical; not tough or hardy. He ambled around, smirking down at everyone, as if he were just so above it all. I suppose, technically, he was – they are very tall. Sure, one could argue that I have spent a good deal of time learning a lot of mostly useless facts about camels. I suppose that is true. But here’s the thing – I love useless facts. And now, I hope, when you look at a camel, you smile. Just a little.